As loneliness reaches epidemic levels, here's how the 15 biggest cities rank

Form Sangsom // Shutterstock

As loneliness reaches epidemic levels, here’s how the 15 biggest cities rank

In 2023, U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy declared an American epidemic of loneliness and isolation, releasing an extensive advisory on the danger that a lack of social connection causes to health. Loneliness affects more Americans than diabetes or obesity. Being lonely can be more dangerous, too. It increases the risk of premature mortality by 26%, according to researchers cited in the surgeon general’s report, and is as lethal as smoking 15 cigarettes a day.

The problem of loneliness isn’t just an American one—the World Health Organization proclaimed it a global health concern and estimates that 1 in 4 older adults experiences social isolation. Another high-risk group is adolescents; WHO states that 5 to 15% of teenagers worldwide suffer from loneliness.

Though social isolation and loneliness are related and often mentioned together, they are not the same. Social isolation is an objective state of having few social relationships. It’s measured by marital status, number of group memberships, and frequency of contact with others. Loneliness, on the other hand, is a subjective measure and shows the discrepancy between a person’s ideal and actual level of social contact.

The COVID-19 pandemic contributed to this ongoing problem as people across the globe were, by necessity, forced into habits that fostered an increased rate of social isolation. Today, people can increasingly perform many aspects of life digitally, including socialization. Researchers call this phenomenon “cocooning”—withdrawing into the digital world for everything except what scientists say people need most: socioemotional support and connection.

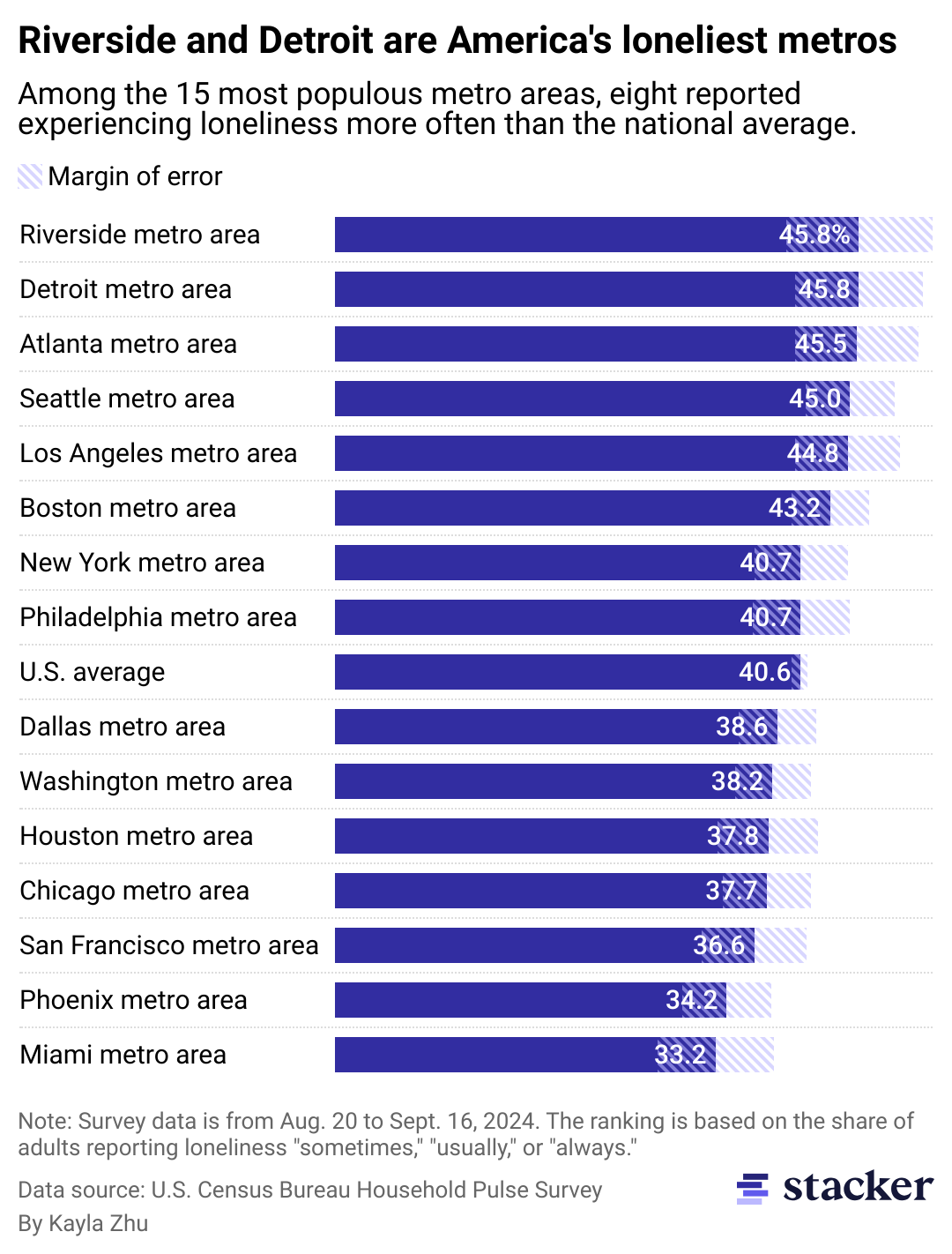

Census data shows about 2 in 5 Americans in 2024 said they deal with loneliness sometimes, usually, or all the time, putting a large portion of the population at higher risk of health conditions. Along with being connected to cardiovascular disease, stroke, and dementia, loneliness has links to other conditions such as anxiety, depression, and suicide. The harm caused by social isolation and loneliness isn’t just happening at the individual level—research shows that the negative impact also affects the larger community. The quality of social connections plays a role not just in individual well-being, but in the health of neighborhoods, workplaces, and schools.

Northwell Health partnered with Stacker to rank 15 U.S. metropolitan areas by the share of adults who reported feeling lonely. Data comes from the Census Bureau from Aug. 20 to Sept. 16, 2024. In the case of ties, the most populous metro area ranks higher.

![]()

Northwell Health

Loneliness is common, even in highly populated cities

According to Census data from September 2024, the metro regions with the highest rates of loneliness are Riverside, California (about 55 miles east of Los Angeles), Detroit, Atlanta, and Seattle. They’re followed by Los Angeles, Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, which all have higher loneliness rates than the national average. Why might some cities score higher than others in terms of social isolation and loneliness?

Many factors contribute to the rise of loneliness—along with the damage done by a global pandemic requiring social distancing, there are many other social, financial, technological, and environmental elements at play.

A study published in 2021 in the journal Scientific Reports shows that cities pose certain risks with overcrowding and population density associated with higher levels of loneliness. That may seem counterintuitive—shouldn’t one feel less lonely with more people around? Research reveals that the presence of other people isn’t always positive and that social isolation is more about a lack of connection than being physically alone.

As of 2018, 83% of the U.S. population lives in urban areas, a number that the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs expects to reach 89% by 2050. As urbanization increases, the spread of metro centers into suburban and rural land results in changes in quality of life.

Sprawling cities demand more automobile dependency, increased traffic and energy use (with more pollution), fewer green and open spaces, and less access to those green spaces. The built environment influences social interaction. Feelings of loneliness can also change in response to environmental factors. Contact with nature, for example, has been proven to lower levels of loneliness.

Also, some populations are more vulnerable to isolation and loneliness than others. Along with older adults and adolescents, high-risk groups include people with disabilities, people living alone (a number that census data shows has increased significantly in both the U.S. and globally), BIPOC, and LGBTQ+ individuals.

According to a 2022 CDC report, among adults in 26 U.S. states, the prevalence of feeling lonely was highest for bisexual and transgender persons, who are also the groups with the highest rate of stress, mental distress, and instances of depression. Loneliness and a lack of social and emotional support are a major threat to the mental and physical health of queer communities.

Vector Point Studio // Shutterstock

How places are trying to combat loneliness

Solutions to combating loneliness and reducing social isolation range, with medical experts pointing out that different life stages require customized strategies. Loneliness has a general pattern, according to a Northwestern Medicine study published in April 2024—it follows a U-shape, higher in adolescence, decreasing in middle age, and then going back up among older adults.

Other variables—including location and gender, racial, or ethnic identity—may also put people at a higher risk. Loneliness affects a significant part of the U.S. population, and its mental, emotional, and physical effects on the health and well-being of individuals and the communities they live in are dire. Hence, the surgeon general’s advocacy of investing in social connection, social infrastructure, and cultures of connection.

Investing in the development of green spaces such as parks, gardens, and trails is one proven way to build social cohesion and connection within urban areas. Medical experts like Dr. Daniel Knoepflmacher at Weill Cornell Medicine advocate for policymakers and planners to support the creation of public spaces where people can come together to share experiences such as music, art, and the outdoors.

But solving loneliness isn’t just about building more spaces. It also includes a host of subtle interventions that allow people to reconnect. A 2023 Bloomberg article written by Linda Poon highlighted West Palm Beach, Florida, urban planning firm Happy Cities. The firm made strategic changes to the environment, such as displaying historical photographs in public to give people something to discuss and placing movable chairs and tables to create microspaces for lingering. In Salem, Massachusetts, “happy to chat” benches were installed with placards inviting people to sit if they wanted to converse with someone new. Similar programs were also rolled out in Sweden and Berlin.

“The key thing about encouraging social relationships in a building is to give people more chances to bump into each other, but also feel like they have some control to leave if necessary,” Houssam Elokda, managing principal at Happy Cities, told Bloomberg.

Even checking out at the supermarket is a prime opportunity to connect. In the Netherlands, supermarket chain Jumbo has checkout lanes that are meant to go slow, encouraging people to chat with each other and the cashiers. These are the types of everyday encounters become rituals that can help people feel connected as journal entries submitted to the Pandemic Journaling Project at the University of Connecticut show.

Designing cities for humans, not cars or business interests, is key to more community spaces where the public can interact and engage in real-life activities.

Story editing by Carren Jao. Additional editing by Elisa Huang. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.

This story originally appeared on Northwell Health and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.