Legal experts discuss how Valentine’s Law cases may play out in court

JEFFERSON CITY, Mo. (KMIZ)

Mandatory jail time and what juries get instructed to consider could guide the first uses of a new state law on car chases with police, according to legal experts.

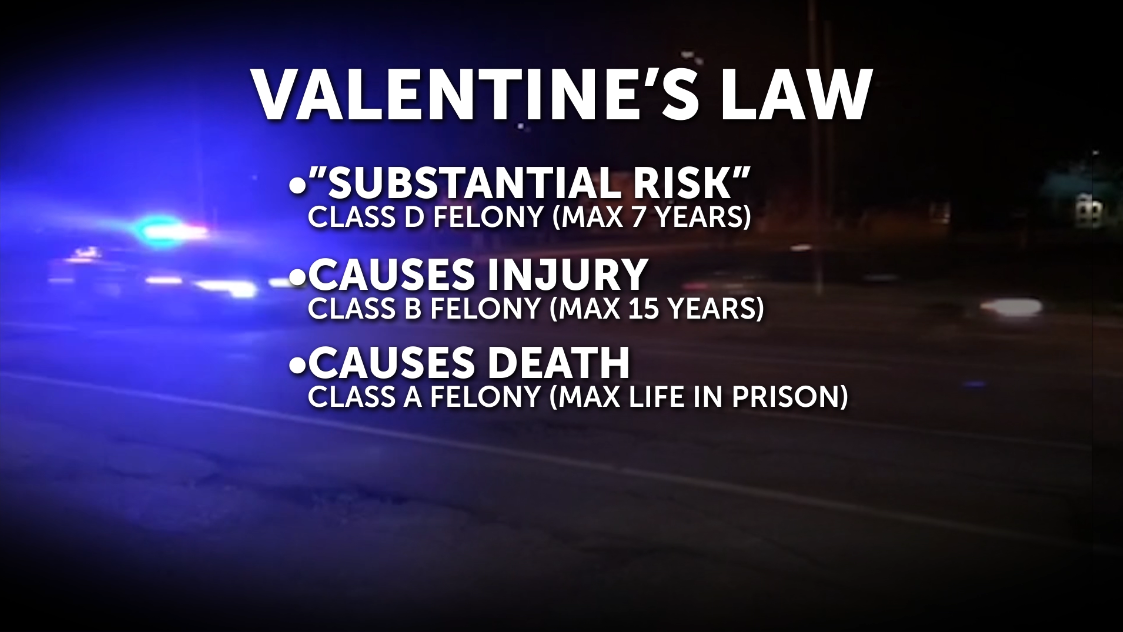

Prosecutors can now consider charging people with aggravated fleeing a stop, dubbed Valentine's Law by state lawmakers this session. People who drive away from law enforcement trying to stop them face the possibility of a class D felony, which also carries a mandatory year in jail, if convicted. The range of punishment increases if someone gets hurt or dies during the chase.

At least two Mid-Missouri prosecutors have made use of the new law since it took effect on Aug. 28. Camden County prosecutors charged 23-year-old Christopher Wehmeyer for allegedly driving away from officers trying to pull him over for speeding.

Osage Beach police officer Phylicia Carson died in a crash when she reportedly lost control of the car on Highway A. Prosecutors in Boone County charged a man for allegedly hurting a state trooper when he drove over the trooper's spike strips during a chase on Interstate 70.

A key element of the new law is proving that the person running from law enforcement created a "substantial risk" to others. Darrell Moore, director of the Missouri Office of Prosecution Services, told ABC 17 News that the new law increases the consequences of traditional chases. Suspects often faced the class E felony of resisting arrest in many cases -- which has a maximum sentence of four years in prison. The increased charge and the threat of mandatory jail time could deter people from trying to elude police.

“Hopefully word will get out on the street and people will realize that this isn’t the old days where maybe I get to run from the cops and maybe get a slap on the hands, you’re talking serious prison time," Moore said.

Defense attorney T.J. Kirsch noted that the mandatory jail time takes discretion away from judges when it comes to sentences.

The threat of that jail time may give prosecutors better leverage to make plea deals on weaker criminal cases. He said judges often know the individual criminal cases best, rather than lawmakers attaching the mandatory time.

"The discretion for the courts is gone as soon as there is a substantial risk to anyone else," Kirsch said. "That's without regard to the length of the pursuit, how that substantial risk is proved, what that substantial risk is."

A person can face an aggravated fleeing a stop charge for driving away "at a high speed" or driving in a way that creates a "substantial risk." Moore and Kirsch said prosecutors can prove that risk in various ways.

"It could be are you in the other lane, are you crisscrossing, are you jumping over medians, are you driving through people’s yards? You can look at that, those are the kinds of things that a prosecutor would argue," Moore said.

The case's fact-finder, either a judge or jury, will ultimately decide if someone's behavior of fleeing police caused another person's injury or death. Moore said the jury will receive instructions detailing those questions when they deliberate a case. But the intent of the person running from police likely won't play a factor in their deliberation.

“There’s no allowance for ‘Did he intend to kill anybody, did he intend to injury anybody, was his actions the direct result?’ That’s not a requirement," Moore said.

Kirsch said higher courts are unlikely to reverse a decision based on arguments questioning those connections.

"The bar for causation in a criminal case is pretty low, it’s going to be heavily reliant on the fact-finder, whether the judge or jury thinks the flight is the cause and is unlikely to be second-guessed by any reviewing court," Kirsch said.

Prosecutors also need to prove that the defendant knew or "reasonably should know" that a law enforcement officer was trying to pull them over. Kirsch mentioned the 2015 case against Sergei Comerzan in Audrain County, where Missouri State Highway Patrol trooper James Bava died trying to pull him over for speeding. Comerzan was acquitted by a jury after arguing that he did not know Bava was trying to pull him over.

"If you’re miles ahead going way too fast on a motorcycle, the wind blowing, the engine roaring, then it’s reasonable to say this person just didn't know there was an officer trying to catch up with them," Kirsch said.

Boone County Prosecutor Roger Johnson said his office will "generally recommend the maximum sentence and oppose probation for high-speed chases" in cases it handles.