Here are the places where air pollution levels could soon be considered dangerous by the EPA

Canva

Here are the places where air pollution levels could soon be considered dangerous by the EPA

Aerial view of white smoke emanating from an industruial building.

The average healthy person takes about 22,000 breaths per day. But depending on where you live in the United States, going outside for a few breaths of fresh air may be slowly killing you.

Millions nationwide live in regions where air pollution levels exceed what the Environmental Protection Agency considers safe. Children, older adults, people with preexisting heart or lung conditions, communities of color, and low-income communities are among the most vulnerable and most severely impacted by air pollution.

Exposure to air pollution is associated with over 100,000 premature deaths annually, most of those being people over age 65. By race, Black and Hispanic populations bear a disproportionate share of those deaths.

A majority of air pollution comes from burning fossil fuels like gasoline, diesel, oil, and wood. Tiny inhalable particle pollutants—just a fraction of the width of a single piece of human hair—form when compounds such as sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides emitted from power plants, industrial sites, and automobiles undergo chemical reactions in the atmosphere.

The most dangerous type of pollution is fine particle pollution or PM2.5. When inhaled, PM2.5 pollutants can travel deep into the lung tissue, enter the bloodstream, and create an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, respiratory illnesses such as asthma, and even lung cancer.

To better protect public health, the EPA’s Clean Air Scientific Advisory Committee is seeking to make the standards around air quality and pollution stricter, leading to thousands of lives saved and billions of dollars added back into the economy.

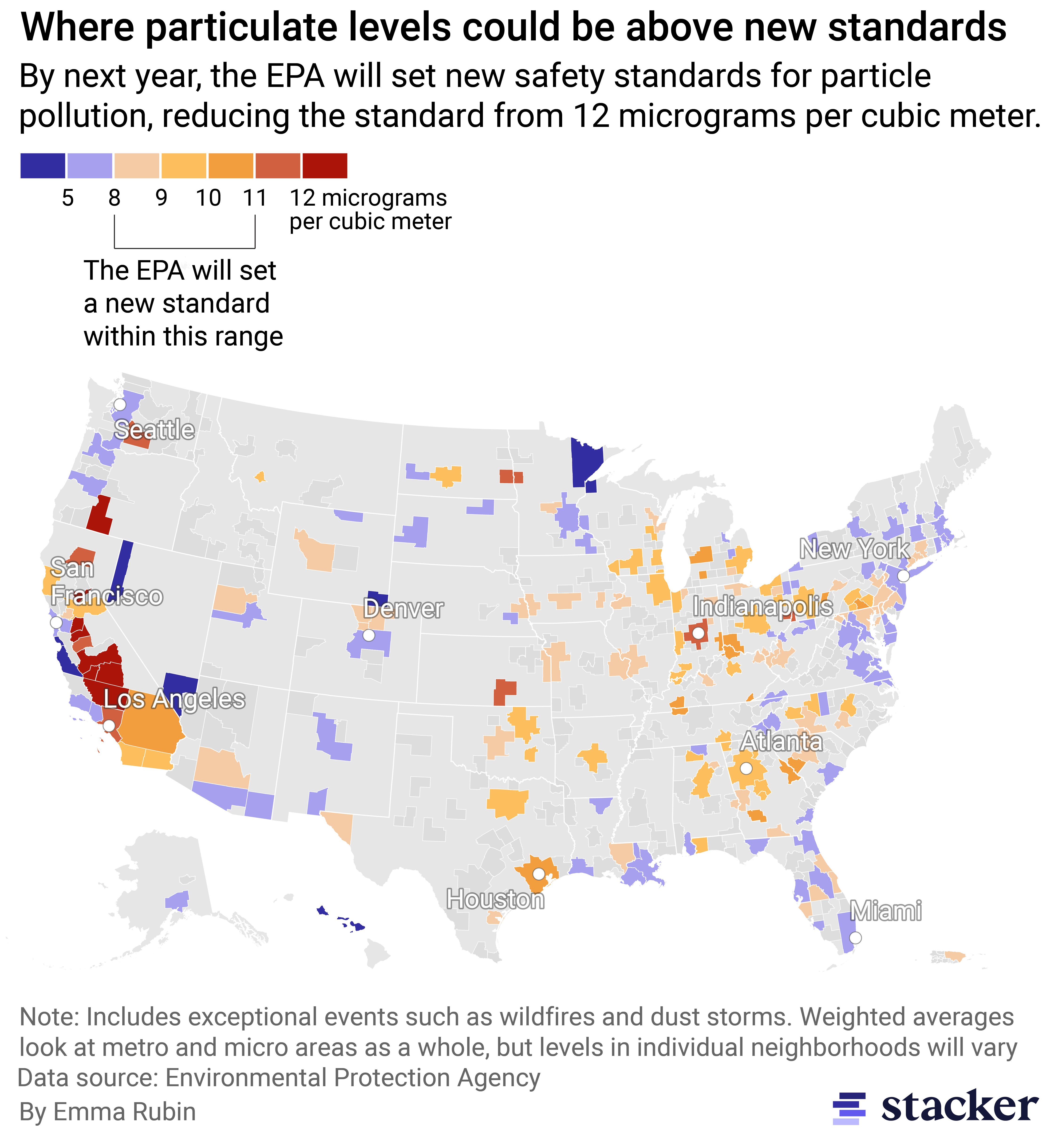

Currently, PM2.5 levels are limited to 12 micrograms per cubic meter of air, as established by the standard set in 2012. The EPA proposes changing that limit to between 8 and 11 micrograms. Even within that range, the impact on public health can vary. A 2022 study commissioned by the Environmental Defense Fund found that an annual standard of 8 micrograms prevents more than four times as many premature deaths as a standard of 10 micrograms. Moreover, many experts, including medical professionals and environmental scientists, do not believe the proposed limits go far enough to address the threat to public health adequately.

Stacker cited data from the Environmental Protection Agency to look at what the agency’s consideration of new particulate pollution standards means for people across the U.S.

You may also like: ‘I have a dream’ and the rest of the greatest speeches of the 20th century

![]()

Emma Rubin // Stacker

At least 12 cities are already above recommended particulate standards

Map of metropolitan and micropolitan areas’ particulate pollution levels.

Race, more than income level, is an indicator of increased exposure to air pollution. In the U.S., PM2.5 pollution is disproportionately caused by non-Hispanic white populations and disproportionately inhaled by people of color, according to a 2019 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

A 2021 study funded by the EPA found that exposure disparities were greater between populations of color and white populations than between people at different income levels. Scientists are unable to definitively identify which emission sources cause this disparity.

Tightening the PM2.5 standard from 12 to 8 micrograms means more people, especially vulnerable communities, will be protected by enforced policy and regulatory measures in those regions as outlined in the Clean Air Act. Currently, 75% of Black Americans are exposed to PM2.5 concentrations greater than 8 micrograms each year, compared to 59% of white Americans.

Currently, 12 cities in the EPA’s data have annual levels averaging over 12 micrograms per cubic meter. If the standard is lowered to 10, an additional 13 cities will fall above the standards. If lowered to 9, at least 32 cities would be above. This data represents less than a third of Census metropolitan areas, meaning other cities with missing data could also find themselves above new standards.

Click here for an interactive table of particulate pollution levels across the U.S. since 2000.

Canva

Air pollution has been linked to respiratory illness, cardiovascular disease, and cancer

A distant view of downtown LA shrouded in smog.

Air pollution can cause short-term effects such as coughing, sneezing, and shortness of breath. It can also cause or worsen long-term conditions, including asthma, decreased lung function, irregular heartbeat, and heart attacks. Studies have shown that air pollution can even lead to lung cancer in people who have never smoked because some air pollutants promote rapid mutations of cells in the airways.

While no one is immune to the dangers of PM2.5 air pollution, children, the elderly, and individuals with preexisting heart and lung disease are especially vulnerable—as are people in low-income communities due to proximity to industrial sources of air pollution, underlying health conditions, and poor nutrition, among other factors. Low-income populations are 49% more likely to live in areas exceeding the current 12-microgram limit than wealthier populations. When exposure levels are looked at through a lens of racial disparity, Black, Hispanic, and Asian Americans are all exposed to levels higher than the national average of 6.5 micrograms. White Americans, by comparison, are exposed to levels averaging 5.9 micrograms.

Black populations are also dying from air pollution at a greater rate than anyone else. Black Americans over age 65 experience three times the number of PM2.5-attributable deaths per capita when compared to other races.

Canva

In some cities, reporting bad smells can help scientists identify sources of pollution

Smokestacks emanating pollutants at sunset.

Air pollution is mostly invisible to the naked eye but can be more easily detected by our noses. Smell My City is an app developed by Carnegie Mellon University’s CREATE Lab that uses crowdsourced reports of outdoor odors to identify potential health risks and sources of pollution.

In an interview with Stacker, Ana Hoffman, director of air quality engagement at the CREATE Lab, said that odor reporting has enabled community engagement on the topic of air quality, and as a result, engagement with many different government agencies, allowing residents to demonstrate, with data, the reality of their lived experiences.

A 2022 analysis of more than five years of Smell My City data revealed several pollution events detected by residents living near industrial operations in the Pittsburgh area. One notable data point was a sharp increase in smell reports described as “About as bad as it gets!” between 2018 and 2019. The source, Hoffman explained, was a fire at the U.S. Steel Clairton Coke Works in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, which took its sulfur pollution controls offline for three months.

“People were breathing raw coke oven gas for that entire time throughout our region. It was not the first or last fire at Clairton Coke Works that happened,” Hoffman added. “There’s several more after that.” Coke oven gas is comprised of a complex mixture of compounds, including carcinogenic hydrocarbons.

Since 2020, Clairton Coke Works has incurred more than 800 fines totaling $4.6 million from the Allegheny County Health Department.