Could 2023 be the year offshore wind energy takes off in the US?

Canva

Could 2023 be the year offshore wind energy takes off in the US?

Image shows a long row of wind turbines protruding from a body of water

On Feb. 22, the Biden administration announced the first auction of offshore wind leases in the Gulf of Mexico. The Gulf Coast, which has been home to numerous offshore oil and gas wells, could provide clean power to 1.3 million homes by the end of this decade. It’s the latest in a recent expansion of offshore wind capacity in the United States.

Two Atlantic offshore wind projects scheduled to open over the next year will grow offshore electric capacity by more than twentyfold. Vineyard Wind 1, located off the coast of Cape Cod, will alone generate 800 megawatts of electricity, making it one of the largest offshore wind farms globally. The second project, known as South Fork, is finishing construction and will supply 130 gigawatts of power to New York later this year or early 2024.

Other projects in states like California and New Jersey and throughout New England are in the planning stage. The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management is also continuing to designate new areas for auction and development for offshore wind power.

![]()

Stacker

The next decade

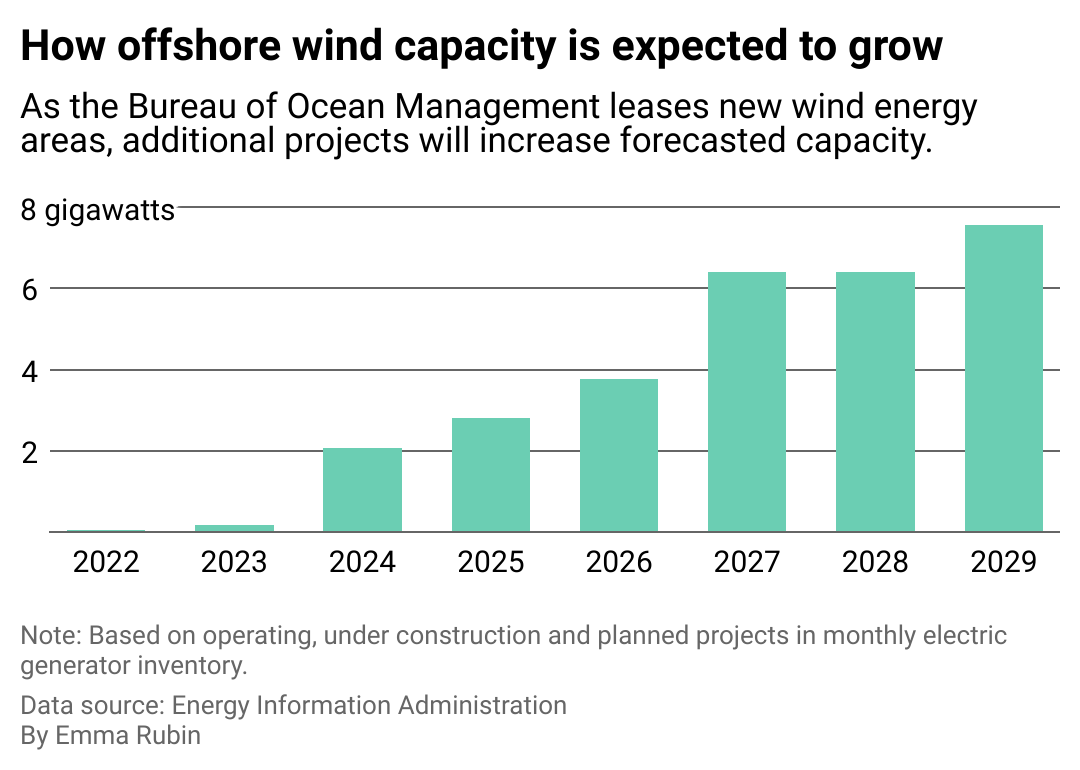

Bar chart showing how offshore wind capacity is expected to grow through 2029

Over the next decade, the capacity of offshore wind farms will grow exponentially, and the Biden administration has set a goal to reach 30 gigawatts of offshore wind energy by 2030.

Globally, offshore wind energy only generated about 12.5 gigawatts of energy in 2022, according to the International Energy Agency, making the administration’s goal a significant leap in capacity. Right now in the U.S., there are two pilot offshore wind farms in the U.S. that contribute 42 megawatts to electric grids in Virginia and Rhode Island. There are over 40 gigawatts worth of offshore wind projects in the full pipeline, from initial planning to fully operational stages. Nearly 20 gigawatts were in the permitting review stage as of May 2022.

Approving offshore wind projects is often a lengthier process than that of onshore. Whereas most land-based farms are on private property, the ocean is considered public land, meaning projects are subject to approval from all federal agencies with jurisdiction such as the Coast Guard, the Department of Defense, and the Federal Aviation Administration.

The Bureau of Ocean Management first designates wind energy areas, selected based on energy potential and impacts on the ocean and environment, and assigns leases to developers with whom the Bureau works to navigate the permitting review process. Environmental surveys are then conducted ahead of making wind energy areas available for leasing. Any construction plans submitted are subject to an environmental impact statement performed by the BOEM as mandated by federal law. Current regulations consider bird migration routes, duck-nesting habitats, and other factors which impact the ocean and marine life.

Stacker

Where offshore wind energy could thrive

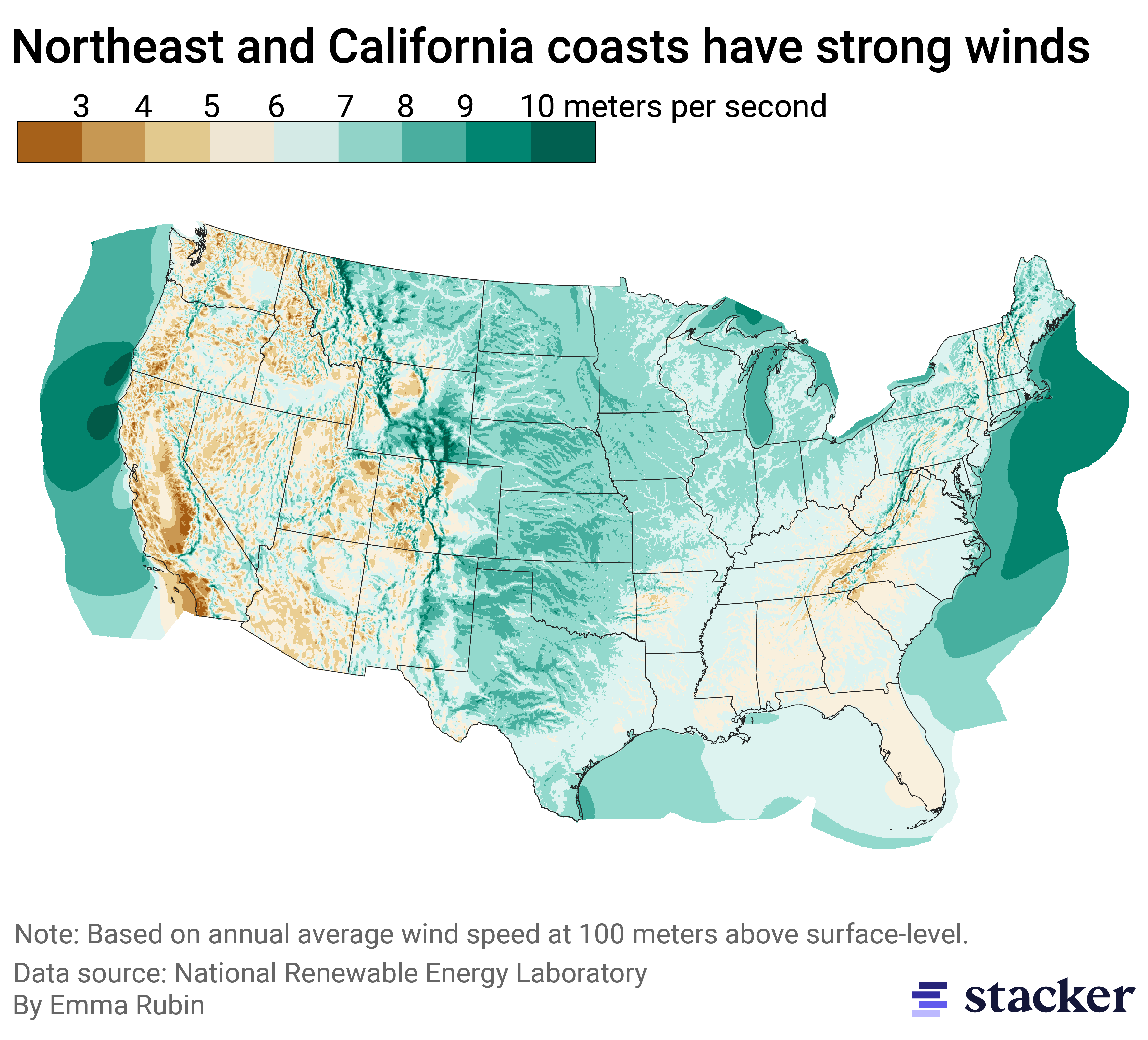

Map of the U.S. showing average annual windspeeds. California and New England have the highest.

Offshore wind projects tend to be best suited for areas where land is less available and more expensive. Generating a gigawatt of wind can require 250 square kilometers of open space.

Walter Musial, principal engineer at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, told Stacker that some East Coast states are increasing dependence on offshore wind in future electricity portfolios for just this reason. “They can base their long-term needs on offshore wind a lot easier because there’s more of an abundance of the resource,” he said.

There are currently licensed wind energy areas along much of the Atlantic Coast and the Gulf of Mexico, as well as parts of coastal California, Oregon, and Hawaii. New England is a popular region for offshore wind projects because it doesn’t have the same amount of open land as a state like Colorado and its coastal region produces powerful wind speeds.

As offshore capacity expands, costs are expected to go down, replicating a pattern that’s been shown with other renewable technologies like solar.

“What we are going to accomplish with these first few projects is a step up to commercialization and cost competitiveness,” Musial said.

Future offshore wind farms could rely on techniques that let them go even further into the sea. All construction projects currently approved use fixed-bottom foundations, generally suitable for shallower waters. In December, however, BOEM auctioned the first commercial leases for floating offshore platforms, which act similarly to buoys. The Morro Bay area, designated last year by BOEM, is over 1,000 meters deep in some areas, making a fixed-bottom installation impractical. Research to identify the best methods to deploy floating technologies and deliver electricity back to the mainland with minimal environmental impact is still ongoing, but it opens up sites for energy development which may have fewer conflicts than areas closer to the shore.

The Biden administration wants at least 15 gigawatts of offshore wind capacity to be generated by floating platforms—this ties into the administration’s goal for 100% carbon-free electricity generation by 2035. The Department of Energy recently hosted a summit focused on advancing the technology and lowering the cost in order to meet that requirement. And while offshore wind is unlikely to ever represent the majority of electricity generation in the U.S., its growth is expected to be an important part of the overall picture.

Other renewable energy sectors have experienced rapid expansion over the past decade. The amount of electricity generated by wind in the U.S. has grown by over seven percentage points since 2012, and solar saw a 3.5 percentage point increase.

“In the full decarbonization scenarios that we’ve looked at, we’re going to need everything,” Musial said. “We’re no longer choosing which kind of energy we’re gonna depend on. We need a diversity of renewable energy.”