More Americans are using air conditioners than ever before—here's what that means for the power grid

Andrey_Popov // Shutterstock

More Americans are using air conditioners than ever before—here’s what that means for the power grid

A homeowner watching a technician install an air conditioner.

As temperatures rise across the country—2022 posted the third-hottest summer on record for the U.S.—people increasingly rely on air conditioning to stay cool.

The concept of air conditioning came about in the 1840s. Still, it wasn’t developed until 1902, when Willis Carrier developed a system that could control humidity and cool the air in a building. In the 1920s, movie theater owners installed them in their buildings, giving people another way to beat the heat—and a new reason to pay for a movie ticket.

Residential air conditioning came in the form of window units in the 1930s. The development of central AC and a post-World War II housing boom led to AC being a common fixture in homes.

Today, nearly 9 in 10 U.S. households use air conditioning, with three-quarters using a central AC unit. American Home Shield used data from the Energy Information Administration to show how air conditioning usage has grown since 2005 and how it compares across all 50 states. For this analysis, households include all housing units that are primary residences. Vacant homes, seasonal and second homes, and military housing were excluded.

![]()

American Home Shield

Air conditioner usage on the rise

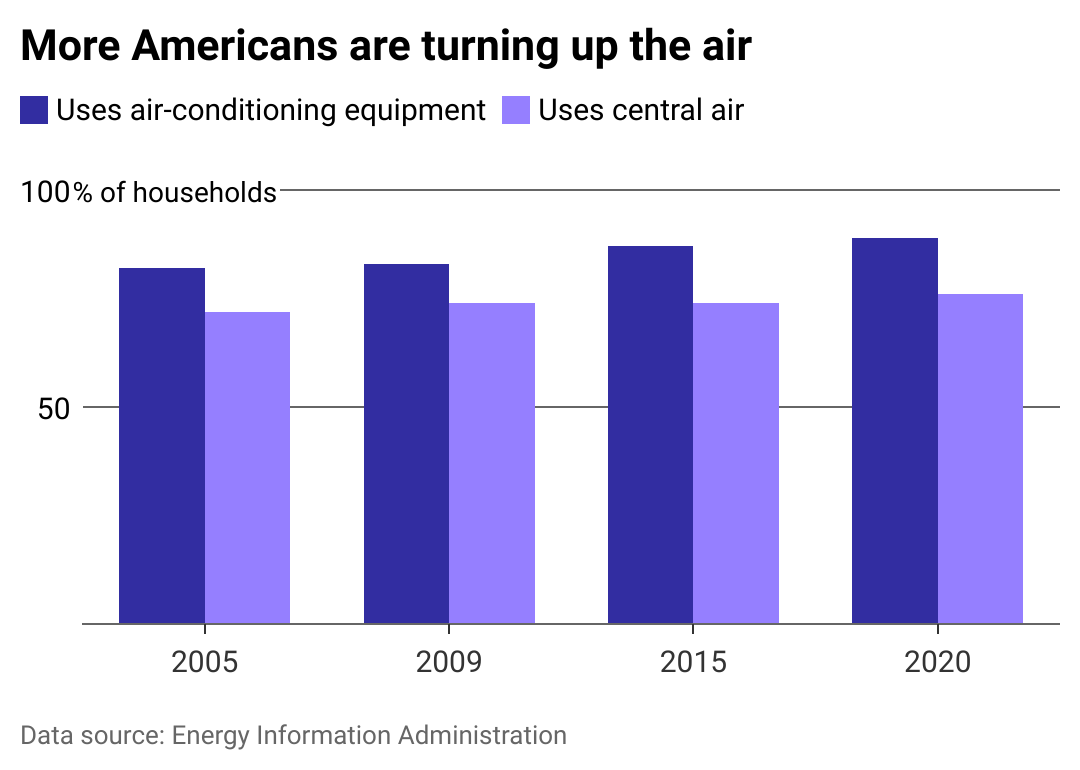

Bar chart showing air-conditioning usage in households between 2005-2020.

Across the country, more states are experiencing hotter high temperatures, but about 45% of the contiguous United States is also experiencing hotter low temperatures, meaning there’s less of a cooling effect from the atmosphere.

Heat waves, or extreme heat events lasting multiple days, have become more prevalent, with “heat wave season” lasting over 72 days, up 36% from the first decade of this century. With an average of over six heat waves a year, air conditioning has become a necessity for many parts of the country.

Today, 22 in 25 housing units (88%) have some form of air conditioning, up from 82% in 2005 and a drastic increase from 68% in 1993. Utilization of central air is also rising as newer housing stock is built—93% of homes built between 2010 and 2020 included air conditioning. Those who rent, particularly in apartment buildings, tend to be those who do not have air conditioning.

American Home Shield

How different states rely on air conditioning

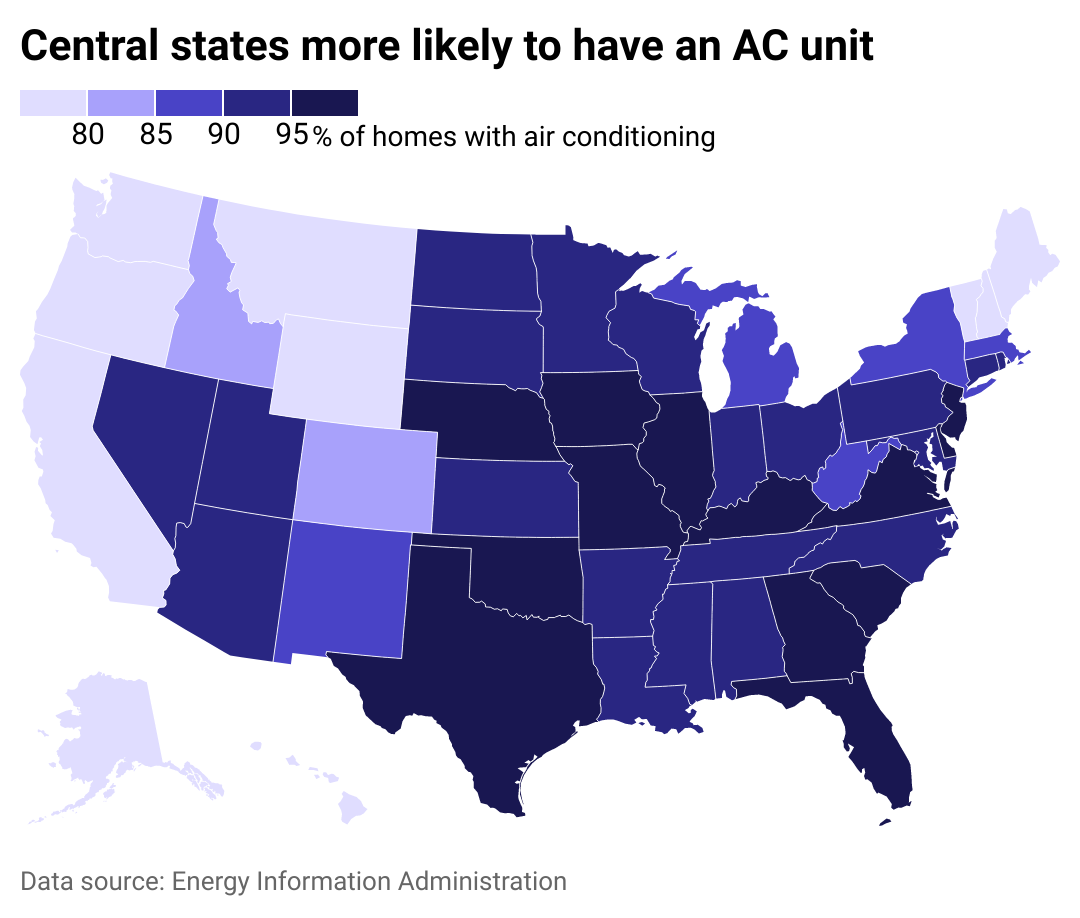

Heat map showing states more likely to have AC unit in the US.

Air conditioning is more prevalent in the central and southern U.S. because of the humidity in those two climates. The Midwest has a mixed-humid climate, which receives more than 20 inches of precipitation annually, but also has an average monthly outdoor temperature below 45 degrees during the winter. The difference in the hot-humid climate of the South is that the temperature is warmer throughout the year. Because air conditioning works to keep humidity at bay, these two regions benefit from it the most.

That said, even the Pacific Northwest’s marine climate is not cooling as well as it used to, causing residents of this area to turn to air conditioning. In Seattle, more than half of homes (53%) had air conditioning in 2021, according to the Census Bureau, a 72% increase from 2013.

Canva

What this means for the power grid

A high-voltage power grid with a sunset in the background.

When everyone cranks their air conditioners, utility companies can struggle to keep up with the demand for electricity. During intense heat waves like the heat dome that covered the West in 2022, air conditioning usage can account for over 70% of peak electricity demand, according to the International Energy Agency. This can tax electricity grids to the point where utility companies have rolling blackouts that temporarily turn off the power in some areas to rebalance electricity supply and demand.

More efficient air conditioners can help ease the burden on the power grid. The IEA predicts energy-efficient units could cut the share in peak energy load from just over 30% to just over 20% in 2050.

This story originally appeared on American Home Shield and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.