Climate scientists tracking how global temperature changes affect Mid-Missouri weather

Decades of evidence proves that the Earth is warming, but to what extent and what does that mean for Mid-Missouri winters?

Researchers continue to study several theories, but many scientists including Doug Kluck, Regional Climate Director for the NOAA Central Region, believe stretches of extreme cold will become less frequent.

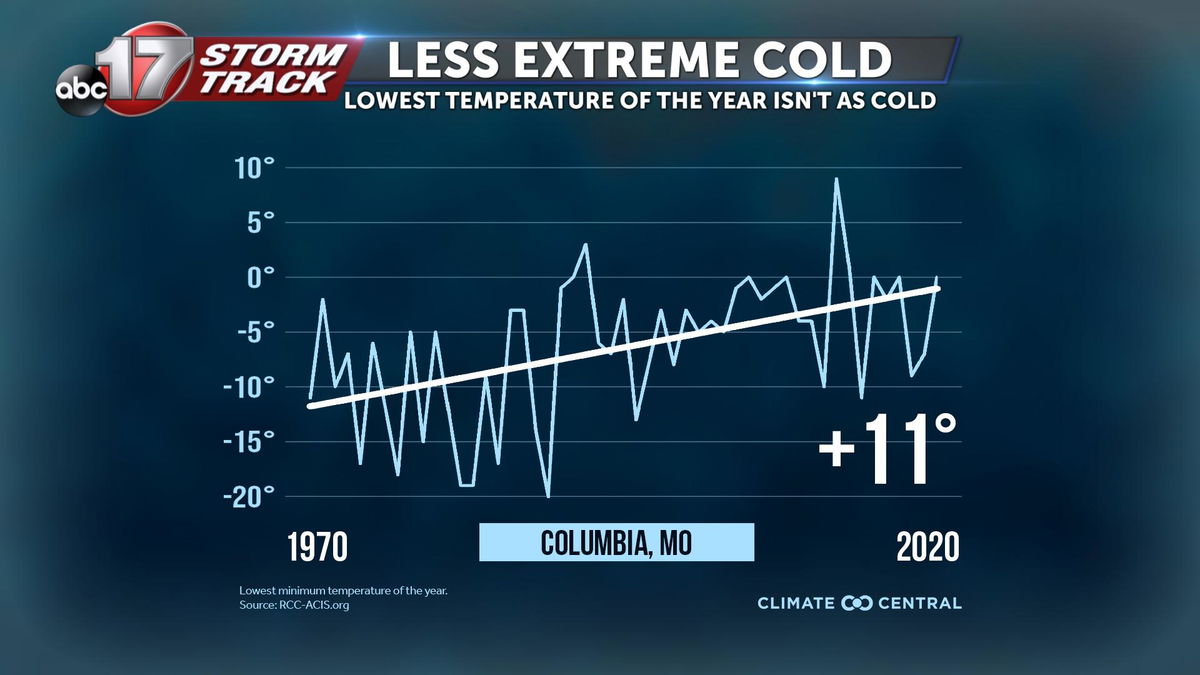

“Minimum temperatures, or low temperatures in the wintertime they’re going up faster than maximum temperatures. So it’s not as cold as it used to be in the wintertime," said Kluck.

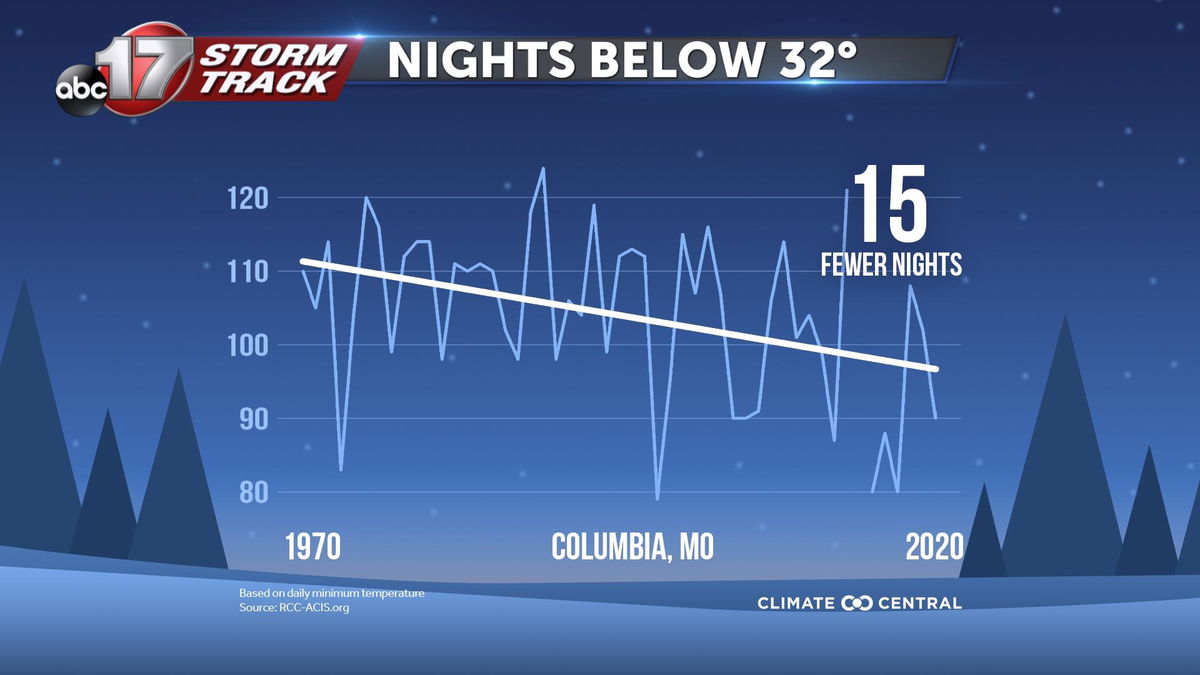

Since 1970 in Columbia, we have recorded 15 fewer nights below 32 degrees since 1970. The lowest annual temperature has risen 11 degrees since 1970.

Cold stretches are always possible given the variability and strength of the jet stream, but the number of days in a row with cooler than average temperatures has also been shrinking; by around 10 days in the last five decades.

But what if warming in the Arctic could actually bring more extreme cold periods in January and February?

Stormtrack Meteorologist Kevin Schneider also interviewed Dr. Judah Cohen, the Director of Seasonal Forecasting at Atmospheric and Environmental Research.

He explains how some research suggests the increase in Arctic temperatures could actually disrupt the polar vortex more often. The polar vortex is an area of low pressure in the stratosphere that is centered at the North Pole, and is tough to break apart or move given the strong circulation of the winds around the low.

Kevin: "Are the two linked? You talked about warming in the Arctic and that polar vortex kind of stretching or breaking down, are those linked in any way?"

Dr. Cohen: "You get a very dramatic warming over the polar stratosphere. So typically you have the coldest air in the hemispheres right over the North Pole and then you can get this rapid warming over the North Pole over 100 degrees Fahrenheit in just a few days. And that’s why it's called sudden stratospheric warming and that can result in either the polar vortex is moved bodily off the North Pole toward one of the continents, or actually the most dramatic types of these disruptions it will split into two … it goes from a parent vortex to these daughter vortices and typically one goes toward Eurasia and the other comes toward North America.”

You may remember the disruption in the polar vortex that crippled much of the country last February, bringing frigid temperatures and power outages that ended up costing almost $200 billion and killing 278 people. Arctic outbreaks of this significance are somewhat rare, but as Cohen mentioned, are worth keeping track of as the Arctic warms.