Climate Matters: Exploring the impacts of multi-year drought in Missouri

COLUMBIA, Mo. (KMIZ)

Mid-Missouri is still feeling the effects of a two-year drought that started in 2022, with 85% of the state still experiencing abnormally dry or moderate drought conditions into the first full week of March.

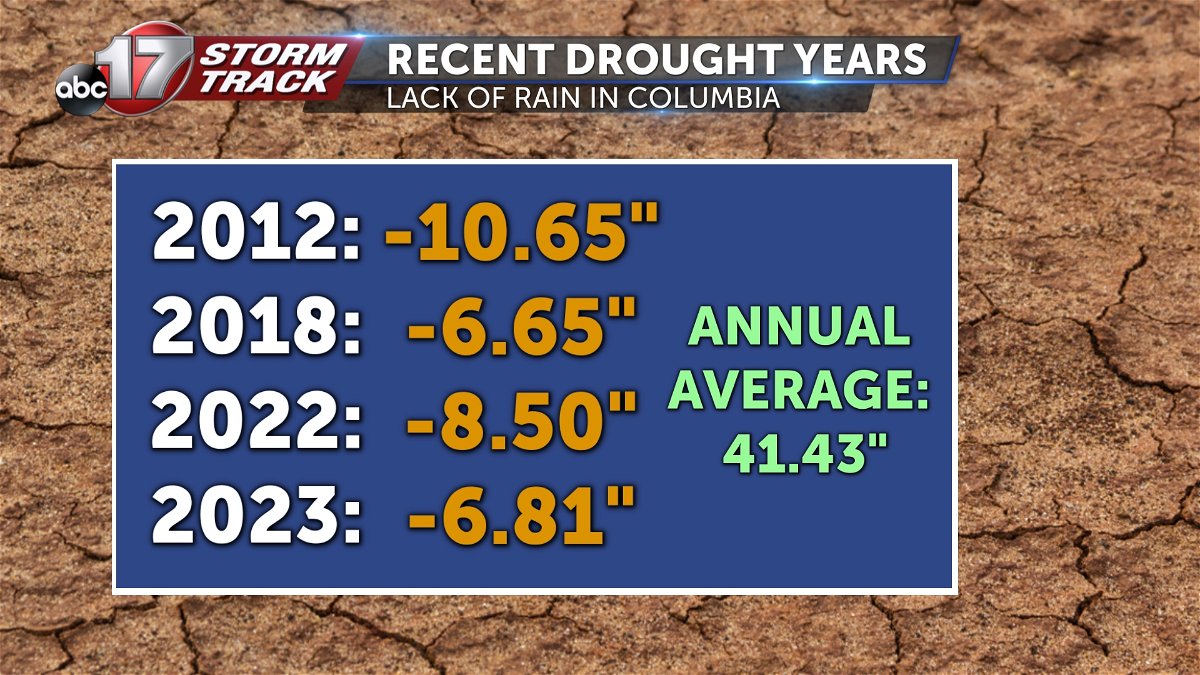

The state has been grappling with a 1-in-20-year drought as April through November 2023 made up the seventh driest growing season since 1895, with 8.15 inches less rainfall than normal. In Columbia, we saw slightly more rainfall than in 2022 or 2012, the most recent drought that most Missourians can remember as also being extremely hot.

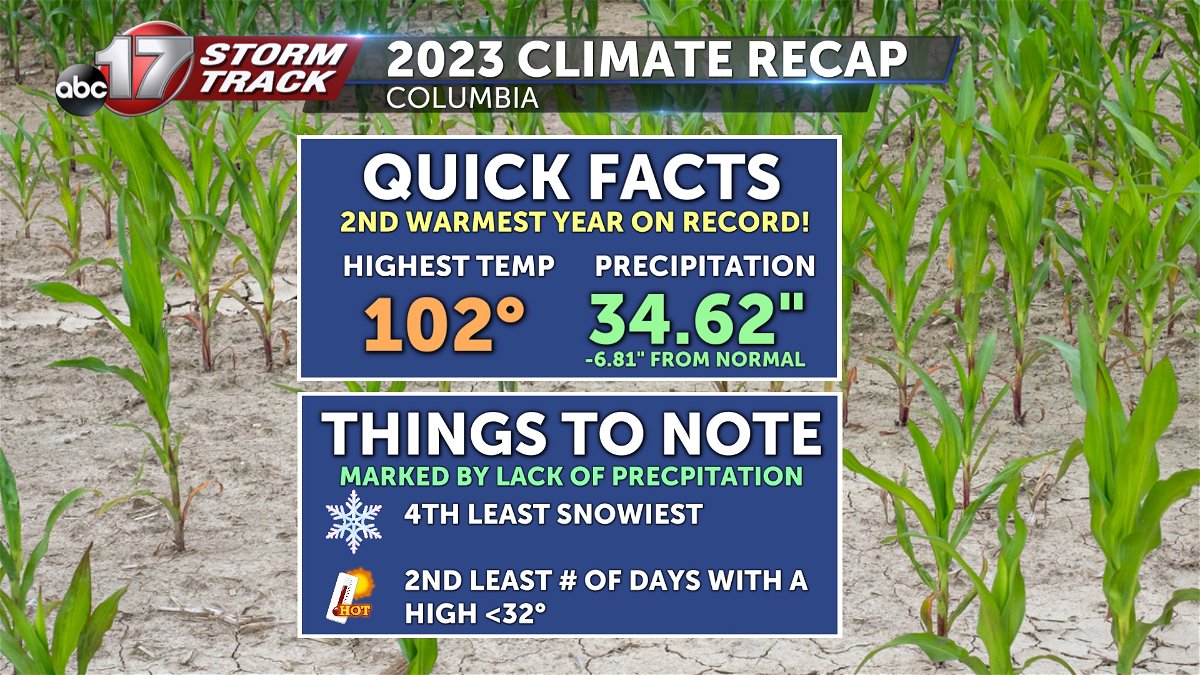

Last year was the second warmest on record in Columbia, with almost 7 inches less rain than average. We also experienced the fourth least snowiest winter on record.

The year 2022 brought more snowfall than average, but spring and summer drought created a large deficit that has lasted into 2024. Last year was the hottest year on record globally, and fifth hottest for the U.S.

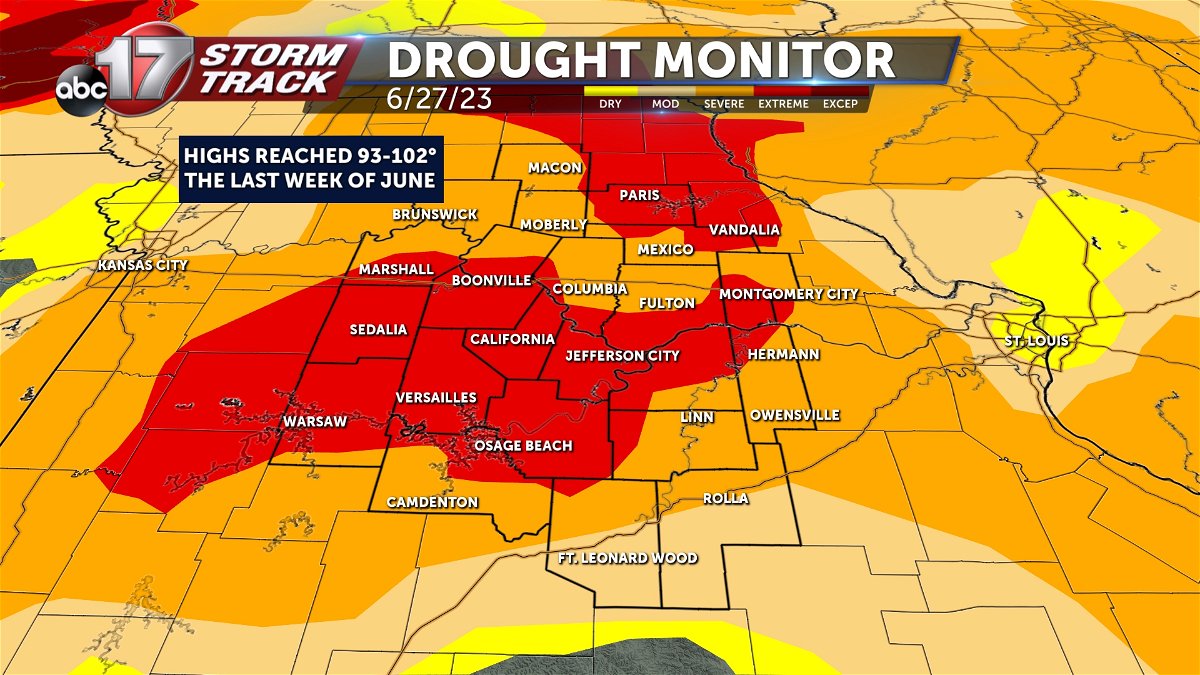

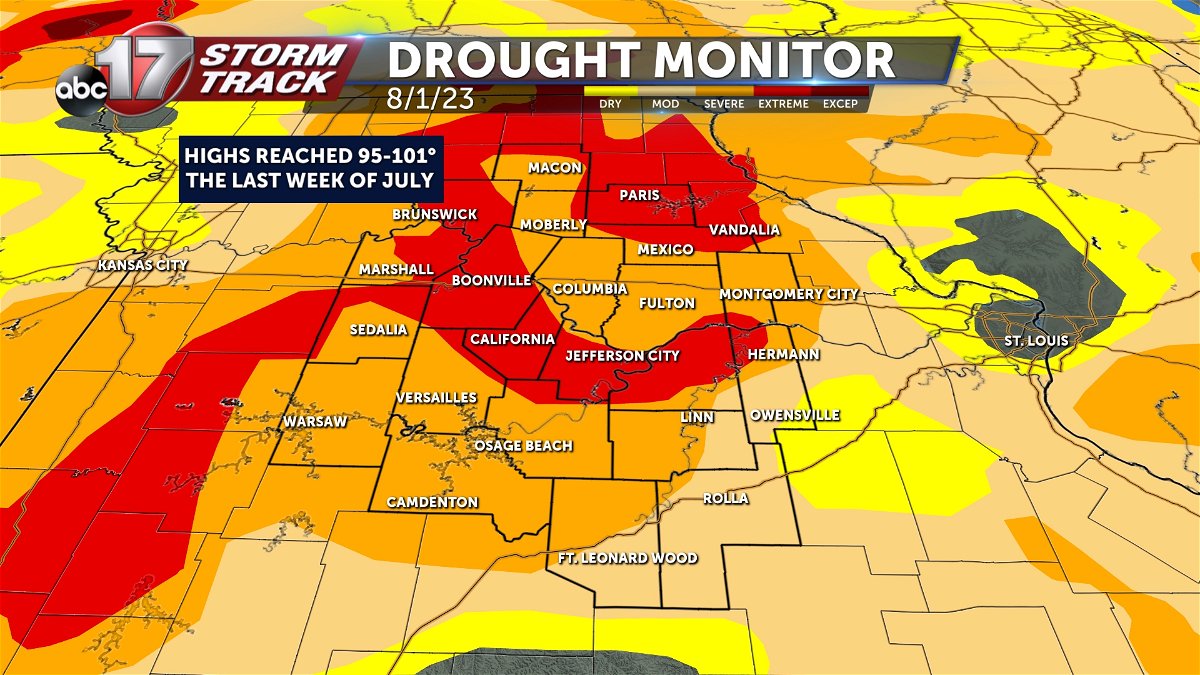

A closer look at climate data shows that stretches of dangerous heat can exacerbate drought impacts. I looked at some of the hottest weeks in Mid-Missouri in 2022 and 2023 and compared those weeks to the drought conditions. The week of July 26, 2022, featured temperatures in the triple digits, with even hotter heat indices. One year later, drought conditions were even worse with temperatures in the upper 90s to low 100s.

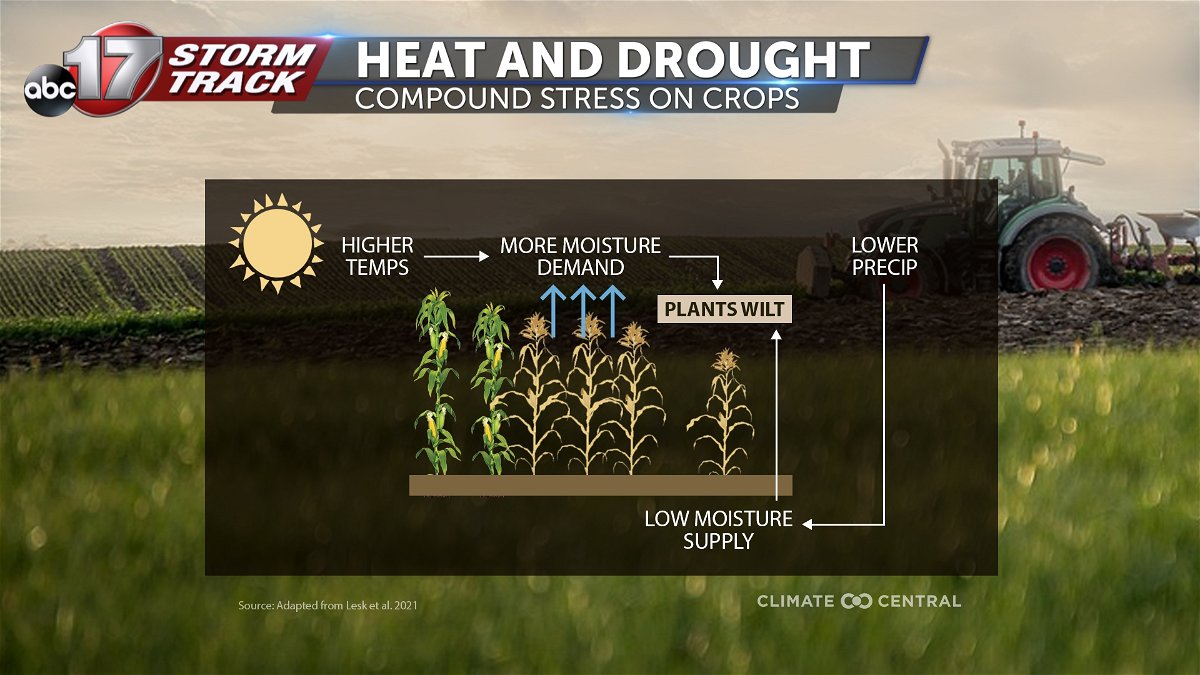

According to Climate Central, extreme temperatures during a drought can put even more stress on crops as plants have a higher moisture demand and soil moisture supply takes a hit. Hotter days typically feature fewer clouds and rainfall, increasing the strain on crops by up to 40% compared to places that experience drought and extreme heat separately.

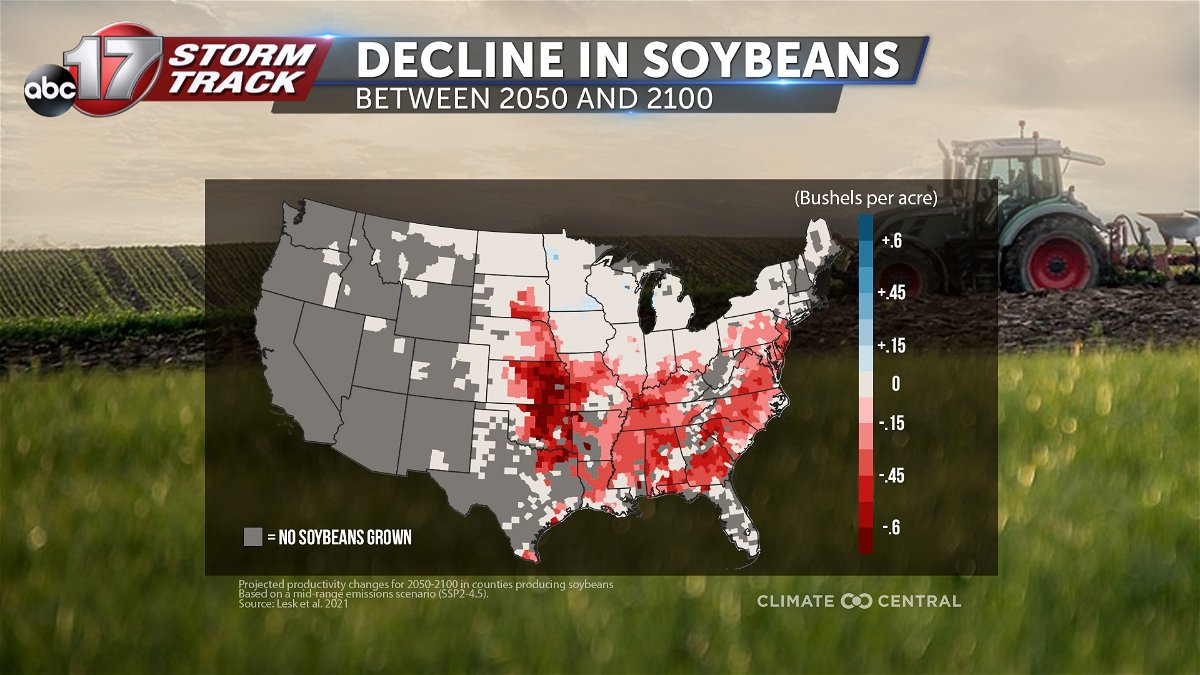

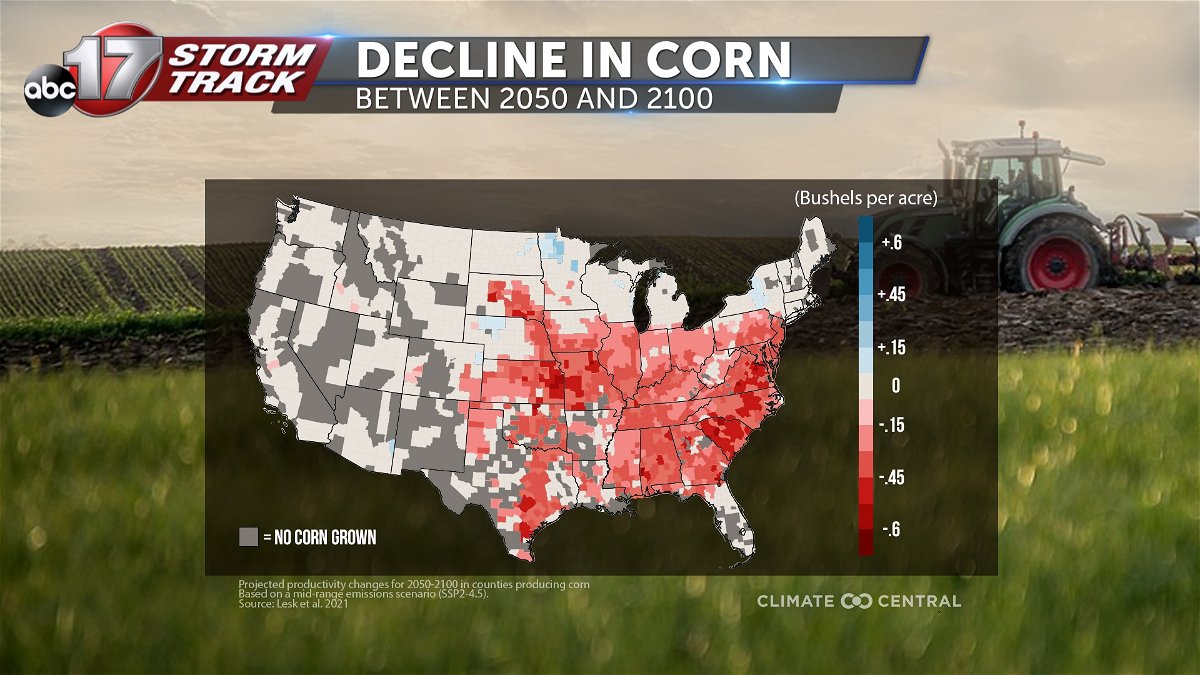

Because of this correlation, climate scientists predict that there could be a 7% decline in corn and a 9% decline in soybeans by 2050 if climate trends continue as they are now. Those numbers could be even higher in the Midwest where evapotranspiration plays a role in decreasing soil moisture.

Evapotranspiration occurs on very hot days when moisture from plants evaporates quickly and dries out the ground faster. We typically find evidence of evapotranspiration on very hot and humid days when weather sensing equipment is near a field of row crops such as corn and heat index readings are very high at that particular sensor.

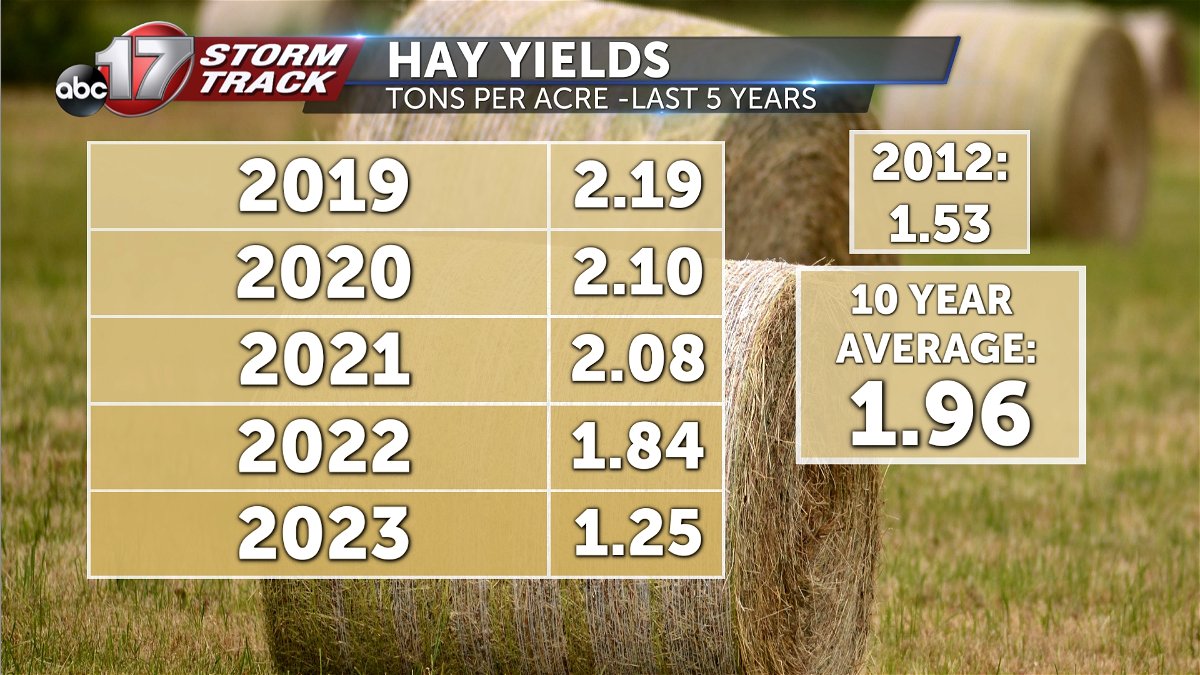

The heat and drought coincide with hard times for farms. There's been a steady decline in hay yields, which has been tough on farmers trying to grow that forage to feed livestock. The number of tons per acre has dropped almost a ton since 2019.

The number of haystacks is at the third lowest in 50 years, according to the USDA.

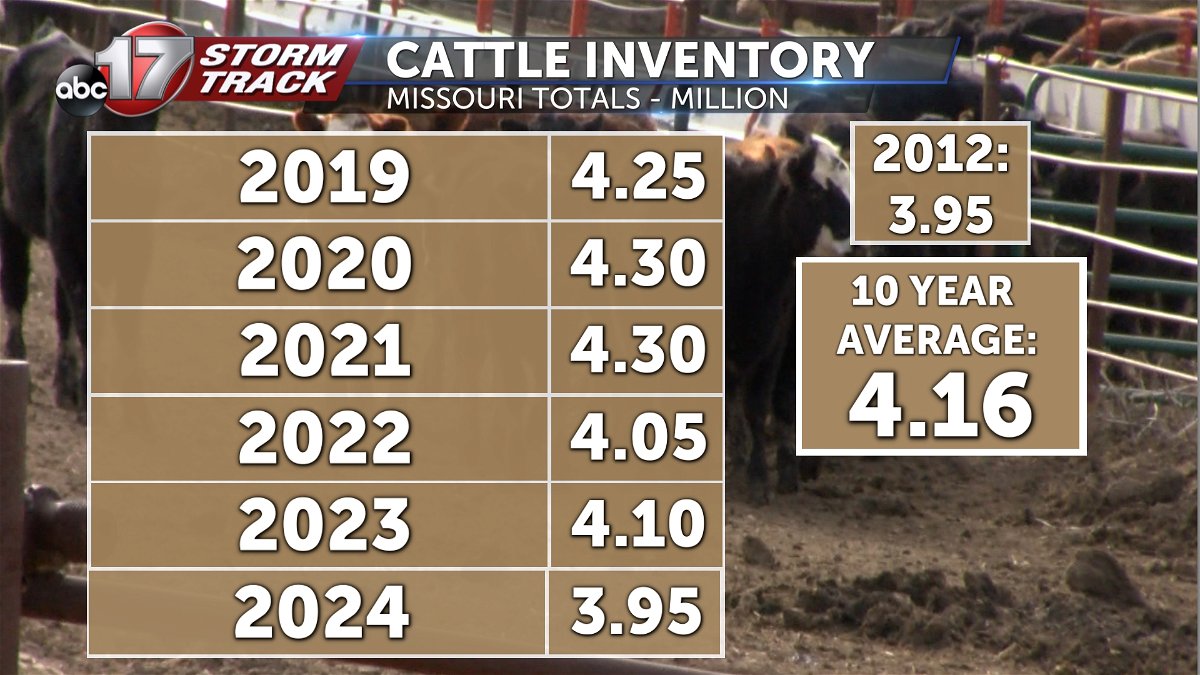

Cattle numbers are also the lowest they've been since 1961. Beef cows are down 2% from 2023, and the USDA Consumer Price Index predicts a 4.5% increase in beef prices at the grocery store after beef production went down almost 5% in 2023 compared to the previous year.

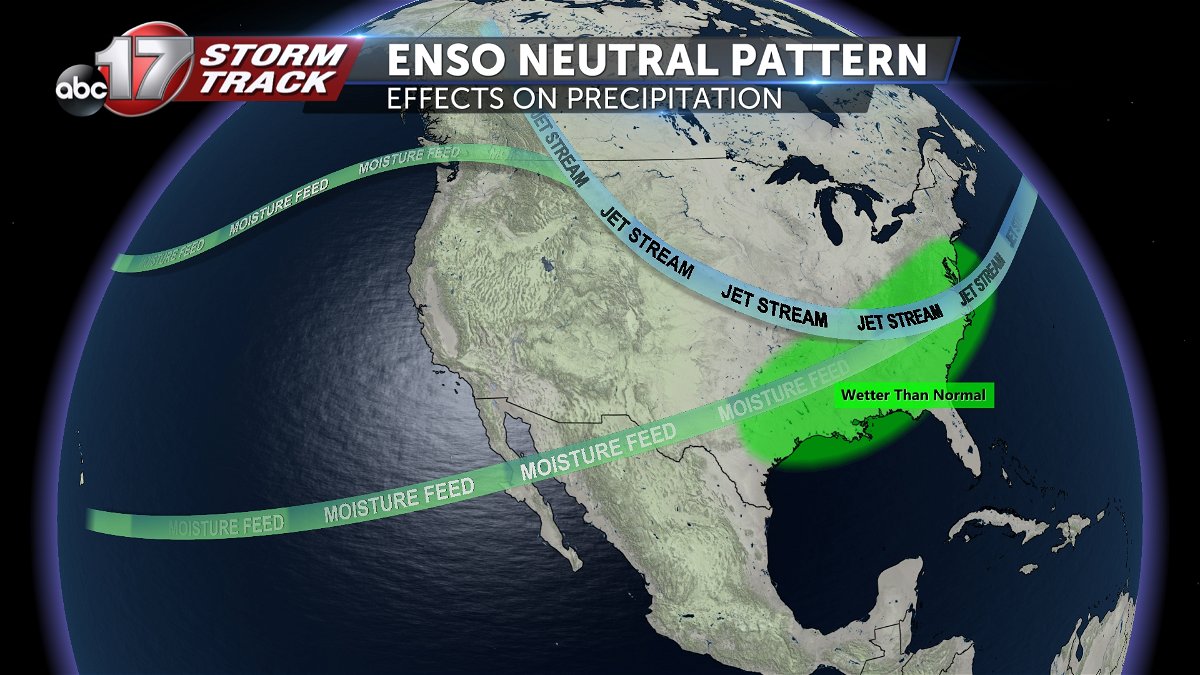

There's a possibility that drought conditions could hang on, but also a chance that things could improve heading into spring and summer. Our global weather pattern is expected to shift from El Nino to La Nina by this fall, meaning the spring and summer seasons will be a time of transition.

Since Missouri is in the middle of the two main jet streams, we could end up with stretches of dry weather along with rounds of storms in the coming months.

In a special Climate Matters report on Sunday after the Oscars on KMIZ, I'm talking to a Mid-Missouri farmer about how two years of dry and hot conditions have put a strain on his operation, from raising cattle to growing corn and soybeans.

I also talked to Gov. Mike Parson about resources that are being made available to farmers right now and what options will be open if drought continues into a third year. I'm digging into how this climate pattern may have an impact on your grocery bill now and in the future.